The story of shipbuilding in Amlwch port during the 19th century is an account of a small, isolated fishing hamlet transformed into a global industrial and maritime hub by the sheer force of the copper industry.

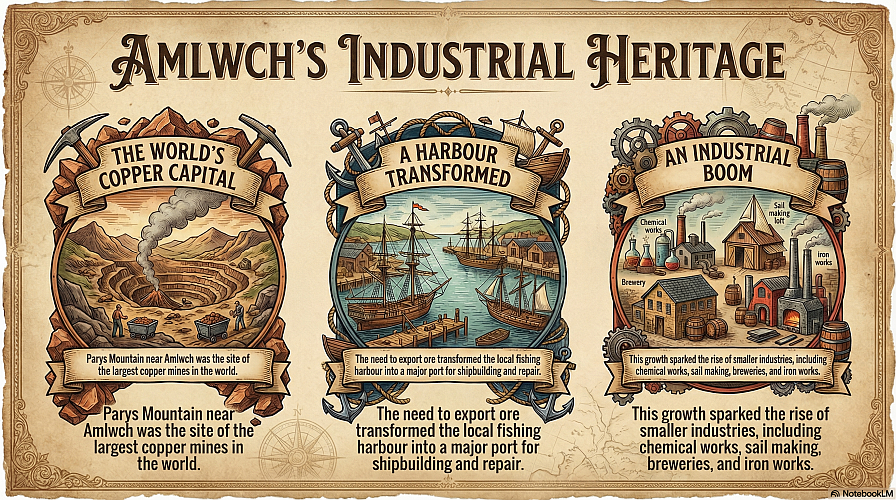

Before the mid-18th century, Amlwch was described as an “inconsiderable hamlet, inhabited only by fishermen”. However, the discovery of a vast body of mineral ore at Parys Mountain on March 2, 1768, necessitated a massive expansion of maritime logistics to transport the copper, ochre, salt, and corn produced in the district. This industrial explosion created a desperate need for a secure harbour and, consequently, a local fleet, laying the foundation for a sophisticated shipbuilding industry that would thrive for over a century.

The physical transformation of the port began in earnest following an Act of Parliament in 1793, which authorized the improvement of the port and the formation of a formal harbour. Under these provisions, the proprietors of the mines oversaw the construction of a pier in 1814, followed by a breakwater in 1822, which rendered the cove one of the most secure and commodious harbours on the North Wales coast.

By the mid-19th century, the port was accessible to vessels of 300 tons’, and a lighthouse with a steady light had been erected to guide ships safely to the quays. This infrastructure allowed for a constant fleet of thirty to forty vessels, ranging from 30 to 200 tons, to be perpetually employed in conveying the mineral produce of the district to warehouses in London, Liverpool, and Bristol.

At the heart of this maritime success was the specialized craft of shipbuilding. The census records of the 19th century reveal a complex hierarchy of masters and tradesmen who inhabited the streets bordering the harbour, such as Turkey Shore, Upper Quay Street, and Machine Street. Prominent figures like Nicholas Treweek, recorded as a “Shipbuilder” in 1861, and Charles Roose, another master “Ship Builder,” oversaw the yards that produced the vessels required for the treacherous coastal trade. These yards were not merely assembly points but centers of high-level technical expertise, as evidenced by the presence of Mine Agents and Mining Engineers like Charles Dyer and Thomas Mitchell, whose work in the copper mines directly influenced the design of transport vessels.

The shipbuilding workforce in Amlwch was diverse and highly specialized. Shipwrights formed the backbone of the construction crews; the 1851 census lists skilled men such as John Hughes, Robert Hughes, Elias Williams, and William Williams. As the century progressed, these families maintained their connection to the trade, with John Hughes (41) practicing as a shipwright on Turkey Shore in 1861. Complementing the shipwrights were scores of ship carpenters, including men like John Evans, Owen Prichard, and Thomas Prichard, who worked on the intricate wooden hulls. This trade was often a multi-generational legacy; for instance, Thomas Prichard (57) and his son Griffith Prichard (31) were both ship carpenters residing together on Machine Street in 1881.

Beyond the timber framing, a fleet required sails and rigging to navigate the Irish Sea. Amlwch was home to a robust community of sailmakers, such as John Davies on Twrcelyn Street and Thomas Crow in the Rhos area. By 1851, the trade was being passed to younger men like Charles Evans and William Evans. The technical complexity of rigging also supported dedicated riggers, including John Griffith and William Hughes, who were responsible for the masts and cordage. The raw materials for these trades were supplied locally by businessmen like John Williams, a ropemaker on High Street, and timber merchants such as William Cox Paynter, who managed the essential supply of oak and pine from his base on Methuselum Street.

The industry was further bolstered by the presence of local iron foundries, which provided the metal components, anchors, and chains necessary for vessel construction. Heth Jones, a prominent iron founder on Methuselum Street, employed a team of men and boys who worked in tandem with the shipbuilders. Other specialized artisans included blockmakers like James Davies on Ednyfed Hill and nail makers like David Owen, who manufactured the thousands of fasteners required for a single hull. Even the port’s administration was deeply integrated into the shipbuilding culture; Harbour Masters such as William Hannell and later James Williamson coordinated the movement of these locally-built ships.

Shipbuilding in Amlwch was not without its risks and economic cycles. Between 1800 and 1811, a depression in the copper trade brought the town to a “state of great distress,” which undoubtedly silenced the hammers in the shipyards. However, the trade recovered in 1811 under new management, and the port saw a resurgence of activity. The types of vessels produced reflected the diverse needs of the Amlwch economy; while the heavy sloops and schooners like the “Jane” and the “Prestatyn” transported copper ore, smaller flats like the “Ann” and fishing boats managed the local fishing and coastal trade.

As the 19th century drew to a close, the professionalization of the trade reached its peak. The establishment of the Literary and Scientific Institution under the patronage of the Marquess of Anglesey provided a venue where the “influential classes” and “mechanics” could attend lectures, likely covering the advancing science of navigation and naval architecture. The census records of 1881 and 1891 show that even as the mining output began to fluctuate, the shipbuilding and maritime trades remained dominant, with large concentrations of sailors, master mariners, and pilots—such as Edward Griffiths and Lewis Thomas—occupying the town’s most prestigious streets.

In conclusion, the story of shipbuilding in Amlwch is inseparable from the mountain that provided its cargo. From the “malignant fumes” of the early smelting process to the secure “secure and commodious” harbour of the 1840s, the port became a self-sustaining ecosystem of wood, iron, and canvas. The legacy of the Treweeks, Rooses, and Prichards—men who turned the local timber and iron into the vessels that carried Anglesey copper to the world—remains the defining narrative of Amlwch’s maritime history.